Remembering Neil Moss…

…sixty years after the tragedy of his death in a Peak District cavern

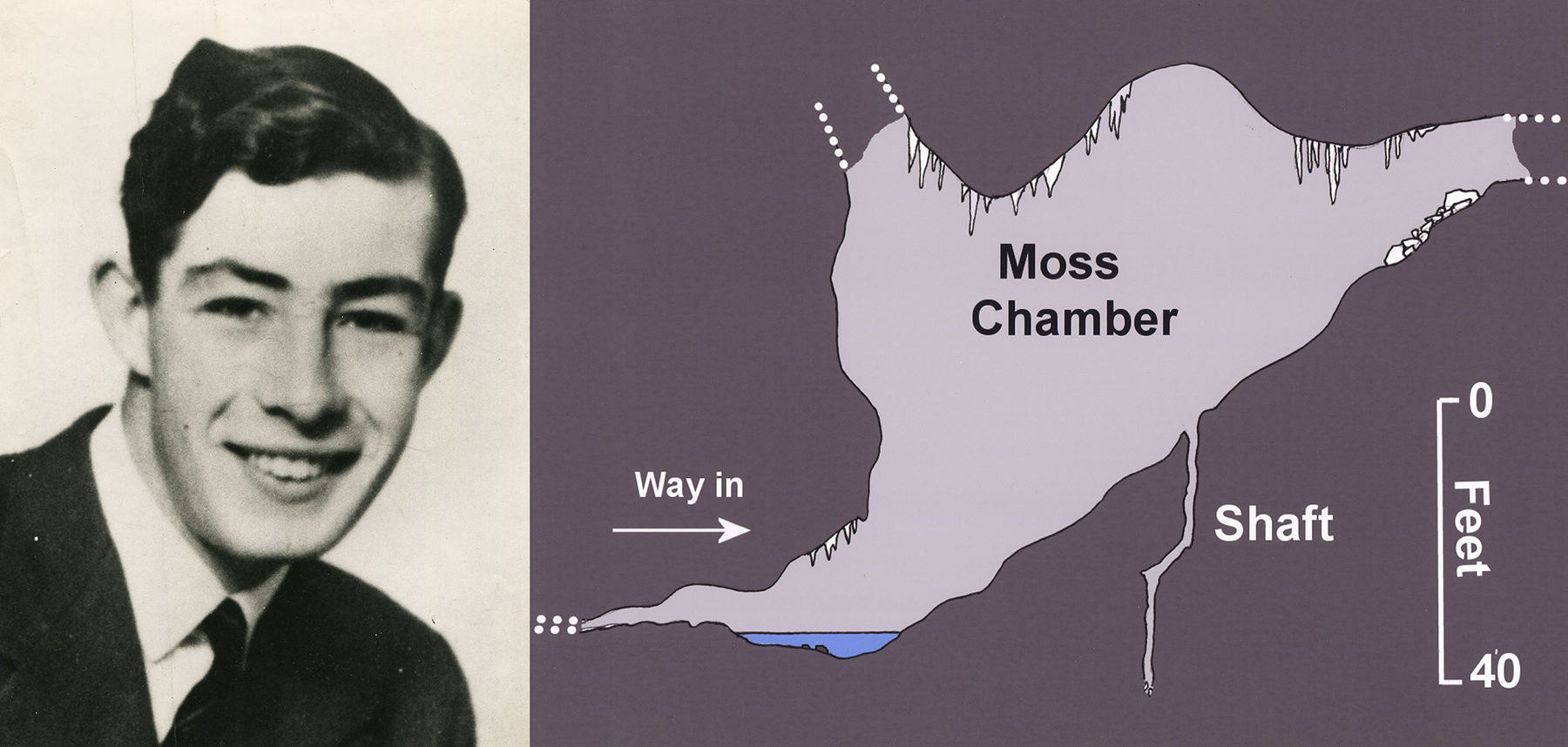

On Sunday, 22 March 1959, Oscar Hackett Neil Moss became jammed while trying to pass down a narrow unexplored tunnel in Stalagmite Chamber – now known as Moss Chamber – in Peak Cavern, one of England’s best known caves with its imposing entrance overlooking Castleton in Derbyshire. In 2006, David Webb’s film about the tragedy set about correcting some of the myths surrounding the rescue attempt by talking to those who were there. Based on an article written by David in 2007, we look back at how the incident unfolded and its influence on cave rescue.

Late in January, an email found its way into the editor’s inbox. An appeal for help. Not for mountain rescue (the days of calling us out by telegram being long gone) but for information. And not about mountain rescue either.

‘I recently read an article on your website [Fight for Life: the Neil Moss story],’ said Pete. ‘I’d be interested to learn more about this tragic event and the brave rescue attempts. I’ve tried to find a copy of the DVD online but have been unable to do so. Having checked your website, I can’t see it listed there either. I appreciate this DVD is a few years old now but I wondered if you had any suggestions for how I might be able to locate a copy? Any help would be much appreciated’.

Well, it’s always good to receive positive feedback – not least for an article published seven years ago – and, as it turned out, we were able to put Pete in touch with the author and filmmaker, David Webb, who also happened to have some copies of the DVD.

All of which reminded us that this year is the sixtieth anniversary of a cave rescue which became a pivotal moment in caving history, the perfect opportunity to retell the tale here. We’ve also stocked our newly-expanded bookshop with copies of the DVD. Just in case.

Moss was a twenty-year-old undergraduate, studying philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford, and also the sports-loving son of a British cotton executive. By all accounts he loved to explore and where better than the vast unknown darkness underground?

He was one of eight cavers from the British Speleological Association who entered the Derbyshire cave that fateful day. Their intention was to explore a passage about half a mile from the show cave, discovered just two weeks earlier. They elbowed, crawled and climbed their way through narrow mud-filled passages, a thousand feet below ground until they reached a larger, open chamber from which a still narrower shaft led almost straight down. Slimly built and six foot tall, Moss was the first to descend.

In Race against Time, Jim Eyre and John Frankland describe how four of the party had been involved in the original exploration. ‘They knew that the tight shaft corkscrewed and was difficult. They had also estimated that the depth of the shaft was approximately forty feet but seventy-five feet of ladder was lowered down the hole in case the shaft continued’.

At around 3.30pm, Moss forced himself into the hole, ‘kicking all the surplus ladder before him. The shaft hung slightly off vertical for twelve feet, then came a difficult corkscrew twist leading to a ten-foot long inclined bedding plane and then a further vertical eighteen-foot drop’.

Thinking he might be able to move the boulders blocking the shaft to one side, Moss manoeuvred himself to a slight recess but in his struggle jammed the loose ladder beneath him. Tired of struggling, he determined to climb out of the shaft, but he never resurfaced. Unable to lift his feet sufficiently to climb back up the ladder he became ‘sandwiched in an elliptical slit only eighteen inches wide’ and asked the others to pull the ladder whilst he held on to it. They succeeded in lifting him a few feet but then the ladder jammed.

Difficulties such as these are not rare in caving and Moss’s companions at first took it for granted that rescue would be a mere matter of lowered ropes and heaving. Gradually, the truth dawned.

Several attempts at hauling him up with ropes ended in failure, each time the rope snapping or shearing on the rock edge. By now the atmosphere was severely polluted, the air flow to the shaft cut off by his body. Moss was clearly becoming disorientated, his behaviour irrational. In The Honour of Being Human, written 25 years after the event, George Cooper, described him as becoming ‘less cooperative’ seemingly ‘unconcerned about the seriousness of his plight’ even suggesting to the others ‘that they go out and eat’.

His rescuers too began to feel the debilitating effects of carbon dioxide. Three of the volunteers lost consciousness whilst attempting to descend the shaft. A fourth, Ron Peters, succeeded in getting a rope around Moss’s chest but this only added to his breathing difficulties.

When a delivery of oxygen bottles arrived at 12.30am, it was in the hope that this would revive Moss and facilitate his extraction. Again and again, his would-be rescuers entered the shaft but were forced back, often themselves in a confused and distressed condition.

As an RAF doctor, waist-deep in mud, pumped oxygen down through a tube, a renewed plea went out – for an experienced caver small enough to negotiate the narrow shaft.

Early in the morning of the second day, eighteen-year-old June Bailey – later described by a British Pathé newsreel as ‘a Manchester typist’ – turned up, eager to make the descent. A number of media reports later described the part she played in the rescue effort, including that her instructions were to break Moss’s collarbones if necessary to free his shoulders. However, none of these can be substantiated, says Webb – though doubtless she did enter the cave.

By early Monday afternoon, almost 24 hours after he had entered the cave, Moss’s laboured breathing could still be heard.

‘We felt we had to try it all again,’ say Eyre and Frankland. ‘Compressed air cylinders were used to try to blow the foul air out of the tube. The walls, ladder and rope were smothered in mud. All that could be seen of Moss was an indistinct muddy blockage far below and he was last reported as being firmly jammed in an unmovable position with one arm forced into a recess under a ladder rung with the effort to free him’.

Meanwhile, others tried excavating the rock lower down, hoping to break through into a lower tunnel, but it soon became clear this was in vain.

The incessant rain was threatening to flood the Mucky Ducks area of Peak cavern. The advice came through to withdraw, for everyone’s safety. When the rain eased off, with one of the RAF doctors to have joined the rescue effort, they returned to the head of the shaft where they had last heard Moss breathing. But this time there was no sound. In Webb’s documentary film about the tragedy, Dr Hugh Kidd describes the experience as the first and only time he had declared death without actually seeing the patient.

Though the exact time of Neil Moss’s death is uncertain, the inquest stated 3.00am on Tuesday 24 March.

His father, Eric Moss, had waited at the tunnel entrance throughout the ordeal and it was he who requested his son’s body be left in place, before anyone else risked their lives. According to those left to clear up, the lower part of the shaft was sealed with a number of loose rocks, collected from the floor of the chamber – not with concrete as frequently reported – and an inscription left nearby.

The Neil Moss story became worldwide news, reported in newspapers in America and Australia as well as here in the UK. On 6 April, Sports Illustrated reported that ‘all was quiet for a while’ as Moss worked his way down, ‘then suddenly from some forty feet below came the terrible, factual statement: ‘I say, I’m stuck, I can’t budge an inch.’

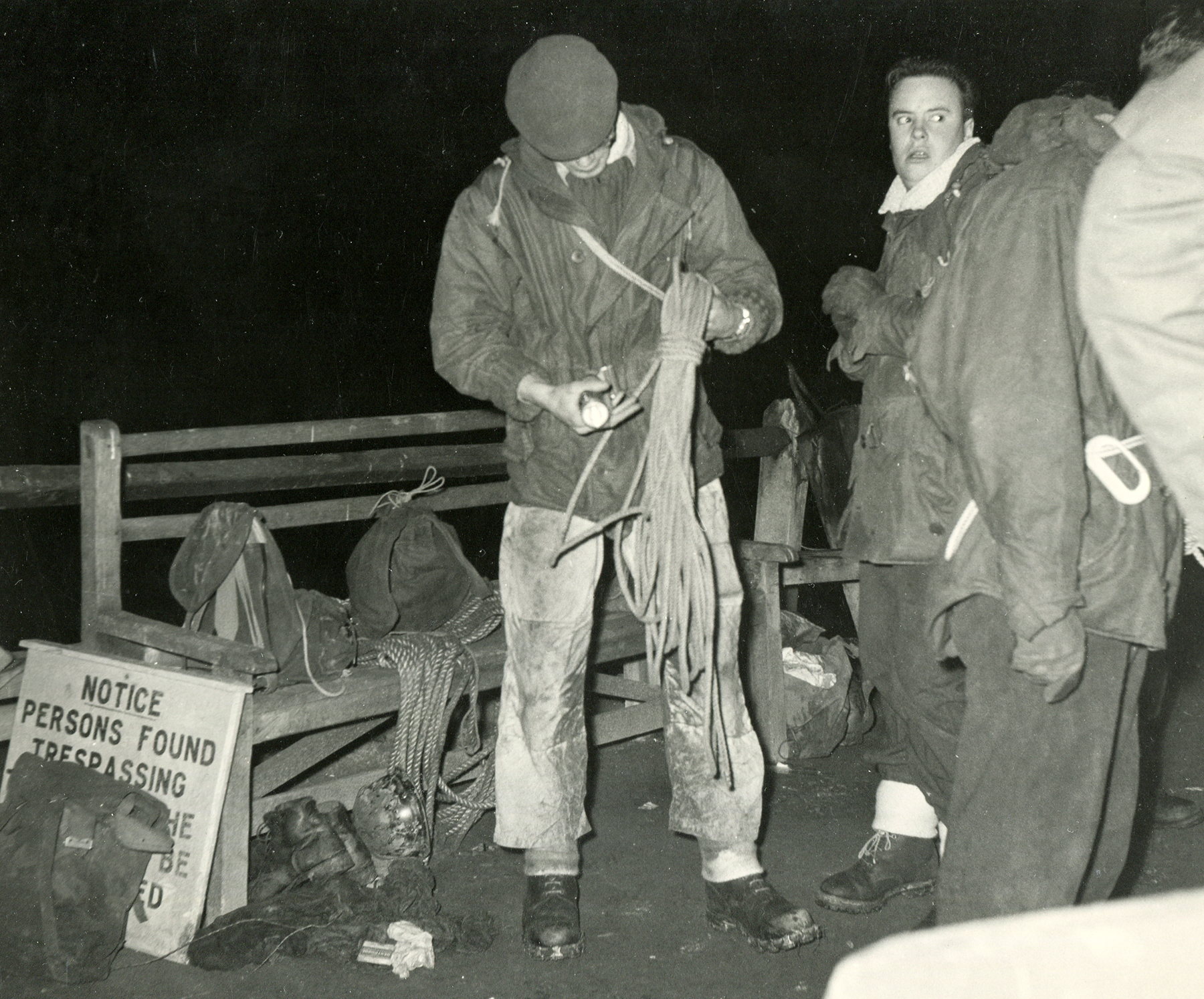

Radio news bulletins went out via the BBC and, within hours, volunteers from all over England responded to the call for help. The RAF, National Coal Board, Royal Navy and dozens of private caving groups had joined in the rescue effort. Sadly, the intense media interest also drew morbid crowds of ‘sightseers’ and fed a number of apocryphal accounts of the event.

The three-day incident had a huge impact on Castleton and its inhabitants, and all those involved in the rescue. In echoes of the Thai cave rescuers of last year, some of the key figures involved received recognition at the highest level for their efforts. In August 1959, Ron Peters was awarded the George Medal, Les Salmon, John Thompson and Flt Lt Carter the BEM.

As a direct result of the tragedy, new procedures for the call-out and coordination of cave rescue began to take shape. Neil Moss did not die in vain, nor will he be forgotten. The story of his death remains a salutary reminder of the fragility of life and the nature of risk.

In 2004, it was retold in the novel One Last Breath by Stephen Booth and, in 2006, Webb – a Derbyshire caver himself – produced his DVD on the story. Filming had begun several years earlier and continued intermittently, but was finally completed late in 2005, following sustained prodding from the principal protagonists. Time was marching on.

‘In 1994, I found myself in Peak Cavern and Moss Chamber. I was already familiar with the outline details of the immense physical and emotional struggle that had taken place there thirty-five years earlier, but the large, well-decorated chamber that housed the tiny shaft which became Neil Moss’s final resting place possessed an extraordinary atmosphere that was impossible to ignore.

‘Here was human drama which had captured the imagination of cavers and non–cavers alike. The fact that, had he lived, Neil Moss would have been the same age as me, was an additional spur to retell the story, through the medium of video, using the recollections of those who were there.

‘The story was already well documented and the announcement to caving colleagues that I was planning to make a film met with mixed reactions. A few thought I’d be opening a can of worms, but most were very supportive and felt the rescue attempt an important part of local caving history and should be recorded for posterity.

‘Despite the heroic efforts in almost impossible conditions, there followed many accusations and counter-claims regarding poor organisation and incompetence relating to the failure to extract Neil. Some of the media coverage was negative towards cavers and caving as an activity. Certain quarters called for it to be banned altogether as irresponsible and dangerous’.

‘I wanted to show the structure and voluntary nature of our rescue services. The Neil Moss rescue attempt was a pivotal moment in caving history. It focused minds and changed attitudes in a manner that helped move the sport towards a more considered approach and became the catalyst for the reorganisation of the Derbyshire Cave Rescue Organisation. I wanted to record the memories and feelings of those who were there and present a study that was as unbiased and factually accurate as possible.

‘Two very full accounts exist – one by Eldon PC member George Cooper (referenced earlier), the other by Les Salmon, one of the rescuers. Both have since died. I was also fortunate to find a box of correspondence between Les and Eli Simpson of the BSA. This included a copy of the police log which revealed the true extent of the three-day operation.

‘My first scoop was to be granted an interview with Bob Toogood, one of the original team, who agreed to be interviewed in Moss Chamber. Spurred on by this, I went on to interview others who took part, each with a different perspective.

‘The only photographs of the site had been taken by well known French caver Jo Berger, which subsequently appeared in Paris Match (although as coroner’s evidence they should not have). My lengthy correspondence with the Paris Match office failed to produce the desired issue. However, I did receive the following week’s edition, which contained an article and photos of the diminutive caver June Bailey who had offered to help. The female angle was picked up on by the media although she had not been allowed to descend the shaft. It was some time later when Ralph Johnson produced a yellowing and slightly dog-eared copy from his attic complete with Jo Berger’s famous photos.

‘Eventually, I also received a collection of old press photos from James Lovelock, author of Life and Death Underground, which contains an illustrated chapter on the incident. He had been a freelance reporter with the News Chronicle at the time. This was the icing on the cake, as the quality and relevance of the photos was outstanding.

‘Having thoroughly enjoyed gathering material, interviewing people and making new friends along the way, I faced the daunting task of actually making the movie. The hardest part was deciding on the structure and a storyline that flowed, with twelve hours of footage to trawl through and a commentary to make, to fit the sequence of photographs. It took almost a year dipping in and out to complete the project.’

And thirteen years after releasing his DVD, it continues to be well-received. If you, like Pete, would like to secure a copy – and support Mountain Rescue England and Wales at the same time – we now have copies available in the shop.

With thanks to David for his proofreading and corrections, and to Pete, who first inspired us to retell this tale.

References: Mountain Rescue Magazine, July 2007. ‘Background to making Fight for Life’ by David Webb. Descent (195), April 2007. Wikipedia. Sports Illustrated. British Pathé ‘Pothole Tragedy 1959’ www.britishpathe.com/video/ pothole-tragedy. ‘Race Against Time’ by Jim Eyre and John Frankland. ‘The Honour of Being Human’ by George Cooper, 1984.

This is fascinating. My Dad used to talk about this rescue and he was one of the volunteers. I’m pretty sure as a nipper I met Les Salmon on one of Dads “expeditions”.

Thanks for taking the time to get in touch Tim. Glad you enjoyed the read.

A few days ago I was recalling this tragic event to a good friend and afterwards did a ‘Google’ search to see if it was listed.

I was one of the small number of Mountain Rescue members from RAF St Athan who immediately drove up to the offer our services in any way we could. With our very limited experience of caving we helped, among other things, to carry the oxygen cylinders as pictured in this article. It was a very tense and stressful time as we all knew there was such a race against time. The feelings returned on reading this article.

I only heard about this poor young man recently. I was moved to tears. I prayed for him that night as I will again this evening. May he rest in eternal peace. X

A good read. My Dad was George Cooper who wrote one of the first write ups, still have the copies of Descent magazine it appears unfortunately he died between the 2 issues it appeared came out.

Thank you. George’s article was a brilliant reference point – incredibly detailed. Great that Neil’s story is now touching a new generation of readers 😉

I was very sorry to read the news about George Cooper alongside the second part of his excellent article on NEIL MOSS: A turning point in British cave rescue. He was a member of the Eldon Pothole Club which has included some of the hardest, most determined British cavers I’ve met. In the same issue of Descent I announced the new discovery which a team of seven of us had taken part in six days earlier in Daren Cilau in South Wales – when we first explored the Time Machine and beyond to Terminal Sump at the World’s End. However, at the time of the Neil Moss rescue attempt I was just four years old and a few months away from my first caving trip into one of the chalk tunnels along the undercliff walk between Rottingdean and Brighton! This was courtesy of a workman who had the key to the door and allowed me to explore inside, where I remember being amazed at how uneven the floor was for my beach sandals.

From the perspective of someone who likes exploring small holes, which has included recovering a survey notebook from a very narrow fissure in a remote cave on Elgfjell in Norway, I’d say the lead which Neil Moss attempted was the most difficult because of the vertical component downwards. The lack of a through draught was also a highly significant factor. Bob Leakey pointed out that the ladder used had rungs spaced too far apart for climbing in a narrow space. In a letter he wrote a couple of issues later to Descent 65, August 1985, Bob stated: “The bottom of the shaft must have had restricted space because both Neil and his acetylene lamp used up the oxygen, which was not helped by those sitting around the top of the hole, whose breath would have drifted down.

When I arrived he was already dead or unconscious. I tried to go down, but just below the entrance nearly passed out. I saw stars and evidently became unconscious for a brief time. If this was how Neil died, it must not have been much worse than falling asleep. Those who pulled me out, full weight, only did so when I stopped answering questions.

Later, when the shaft had been cleared and oxygenated, I went down again, and at about 20ft felt with my boot something soft blocking the shaft at a restricted space. I was then lowered down head first by a rope round my boot. Neil’s body had evidently been pulled up to below the restriction with his back and shoulders blocking the shaft so tightly I could not get my fingers past to feel for his head, or move the jammed ladder.

If I remember right, the upper part of the shaft just above the body was too narrow in places to get two feet on different ladder rungs at the same time. At the same time I had been caving for over a decade, and I remember thinking that had I been going down that shaft on a new discovery the way Neil had done, most probably I too would not have realised the danger and would have done as he did, and with the sort of tackle we used in those days would have suffered the same fate!”

You need to start with small steps exploring new caves – push as far as you’re happy on your own and then turn back to assess the situation, fetch new tackle (if necessary) and re-energise yourself physically and mentally. This is so you are properly ready and prepared for sticking your neck out further than anyone else has yet dared to do, but with the mental and practical preparation that will enable you to bring yourself safely back home again at the end of it all. Several of my good caving friends, contemporary explorers, died by drowning during cave diving operations. Giles Barker, who lent me the ropes that got us over the pitches in Daren Cilau, but was too safe a caver to stick his neck out during the first ascents, died falling down a shaft during a cave expedition to Northern Spain. So, learn to do dangerous things safely in your own time and not when rushed or seemingly put under pressure by others.

I’ve been to Moss Chamber in Peak Cavern and although Neil Moss’ physical remains are there, his spirit remains alive with those who remember him. The lessons learned from his untimely death need to continue to be passed down from one generation of cavers to the next, as was done superbly by George Cooper in his time and has now been well renewed for the internet era in the piece above.

Heres a funny one for you. I live in Adalaide, but used to live in Perth. I was a university lecturer. I headed over to Perth, aiming for an ex-students drive in my campervan, we pulled inand was sorting ourselves out. Mrs next door came out, with an accent just like mine. Where are you from? Buxton she said. Yes, Mrs George Cooper! I had known George since a 12 yo at the surface of the Berger in 1967. My Dad was Doc Kidd.

A huge thank you to everyone who takes the time to add to this story – each comment seems to add another tiny piece to the jigsaw. I sense an updated article may have to follow at some stage, incorporating all these lovely snippets of memory and history!!

Your father delivered me at corber hall maternity hospital in buxton derbyshire ,england at about 6am 9th match 1965. My mum said he still had his pyjamas on under his trousers.

As i understood, he moved to oz soon afterwards.

I’m glad it was him…

Apologies for my tardyness – I have only just seen this. It does not surprise me in the slightest that Da had his PJ’s on under his trousers: this was standard medical practice of the day in a country town! However, Dad never emigrated – I did aged 35, and he and Ma came out at least one a year until death

Small world! Growing up in Buxton I had heard about the caver who sadly couldn’t be rescued. I didn’t know about Dr Kidd’s involvement, but remember him as my family doctor. We also had an art teacher at Buxton Girls School, Mr Brown, who was a caver and who was banned from Peak Cavern as he kept popping up during tours round the show cave part!! He did take us potholing once (6th form age) into part of the the same system near Giants Hole, not far from Eldon Hill. The entrance was out of sight from the farm as I don’t think we had permission to go there.

Hello Aneurin 👋 my name is vicki ,I used to look after you and Saul sometimes when you were little,I hope you are both well 😊

Judy, thank you for the respectful article. I confess to missing the fact that it was the 60th anniversary of his death – the fact that people are still talking about the story means that the impact is still felt, and that, despite the tragedy, valuable lessons were learned which are still relevant today. Whilst out climbing yesterday evening, Alan Ellinson from Rope Race mentioned that he was seeing a lot of articles commemorating the 60th anniversary of the tragedy. It is at this point that I should highlight that Neil was my uncle.

I can’t add much more to the story that’s already been told but thought that I could add some additional context. Neil was the eldest of four children, the other three were either still at school or had just left (they are still alive). Growing up, the events weren’t “not spoken about” necessarily, but my brother and I weren’t aware of the huge international attention and significance of the rescue attempt when we were younger. It was only on an outward-bound holiday (ironically after we’d just returned from a caving expedition) that we were shown a copy of (I think) the Descent magazine article (1987ish?), which brought home the magnitude of the events to us. Google now gives us access to the Pathe News footage, and much more information, and what shines through, more than anything, is the bravery and selflessness of everyone involved in the rescue attempt. This certainly is one thing that was mentioned by the family over the years.

Last year I received a letter from a friend’s mother-in-law who was a young girl in Castleton at the time. Staying off school as she was poorly, she remembers the sirens and the later subsequent activity vividly. In fact Neil had been staying with her Aunt Ruth at Whitelee Farm – a B&B specifically catering for potholers. There were some lovely stories that she also included in the letter: Dr Willis, a rescuer delivered my friend’s wife, and Ken Pearce, another rescuer married a local farmer’s daughter.

Eric Moss (my grandfather) had been in Special Operations during the war and it’s thought that his request that nobody else put themselves in harm’s way, with regards to the retrieval of the body, was, in part, due to the senseless loss of life that he’d witnessed in service (and common sense).

I drive through Castleton regularly on my journey between Manchester and Sheffield and I always take the opportunity to think of him when passing Peak Cavern. As a family we frequently walk around the surrounding hills. I also climb in and around the Peak District but, conscious of family commitments, and perhaps being overly-conscious of the risks of outdoor activities, would describe myself as an “enthusiastic, non-risk taker”.

We attended the Christmas carols in Peak Cavern last year, and whilst it was a fantastic event it was slightly surreal knowing that my uncle’s remains were close by. I suppose if you believe in “that sort of thing” then he would receive great comfort from the hymns and celebrations.

Thank you for highlighting the myth around his remains being concreted in – this is what I was led to believe. The placement of rocks seems more dignified and is comforting.

Once again, thank you for a well-written, respectful piece. And the fact that the lessons-learnt from the tragedy have benefited cave rescues since, give comfort to the family.

David, thank you for such positive comments and for taking the time to respond at such length. It’s always good to know my articles are read and appreciated – especially the lengthier ones! – but even more significant, with stories like this, when the response is from a family member. Such is the nature of history telling that, no sooner have you written it up, something new always comes to light, so lovely to have your words about the family background adding context to the whole. Neil’s story certainly seemed to strike a chord at the time and continues to do so sixty years on. The response both here and through our social media post has all been positive and heartfelt and there’s been a modest revival of interest in the DVD too. Glad I could help keep your uncle’s memory alive. Thanks again.

I am currently trying to write an account of this story based upon the various sources described including a radio interview with the late Tom Tomlinson, who played a part in the rescue attempts, and whom I had the privilege of meeting. Obviously the advent of the internet, and the publication of various accounts as well as video films has made this easier than might previously have been the case. I am anxious to ensure that my account is as accurate as possible, so any assistance would be appreciated.

I’d like to start by apologizing for commenting on such an old post. I’m a speleology enthusiast living in the United States, and I only recently came across this page. I just wanted to thank you for sharing these memories.

I wasn’t alive at the time of the tragedy and never knew Neil, but his story has stayed with me for some time. People often draw inspiration from those who became famous or had decades to build a legacy—but for me, it’s different. Neil’s story—his quiet courage, his curiosity, his intelligence, and the life he was just beginning to shape—has moved me in a way I struggle to explain.

I made and wear a small pendant with his photo—not as decoration, but because carrying his memory feels important. When someone asks who he is, I get to share what little is known about who he was beyond the headlines. In my own quiet way, I try to make sure he’s not forgotten. He inspires me still.

Thank you,

Sonja

I think I was the last caver to be lowered down the shaft. Neil had a ready been pronounced dead. I didnt actually reach him and the decision to get out had been made.

On retreating I managed to avoid all the press and walked out of the entrance on my own.

Thanks for reading and commenting Frank. Good to know the story is still being shared and read too!

Hi

After reading this artical it brings back momemorys I was only 8 when Neil died but I remember it well the caves round Derbyshire I no well ,been in and explored many .

As I young man I used to go to crook stone barn

bottom of kinder scout outward bound centre owed buy British steel where I worked.

We used to go for wkends working and climbing potholeing and walking it was great .

Pot holing was my favourite so no the caves round Castletown.

But when this happened with Neil it was a lot nearer home ,2doors from me lived Peter Crabtree who was a member of caving team with Neil I fact it was Peter who invited Neil to explore the caverns in peak cavern .

I used to talk to peter and ask him about his caving exploits all his caving clothes were always on the line what his mother had washed.

Sadly peter died a few years ago but his wish was to have his ashes scattered at peak cavern to be with his very good friend Neil moss which his did as he wished

Thankyou graham

Hi Graham. Thanks for posting and apologies for the delay in responding – comments have to be approved before appearing and I’ve only just managed to login to the system. Great to hear your memories of Neil and Peter. Neil’s story is easily the most frequently read and commented on here – certainly touches a nerve with people. Good to keep his memory alive – not to mention the remarkable efforts of the cave rescuers. Judy

Doc Kidd was my Dad; I lived with this and several other heroic rescues through my childhood. While some had appalling outcomes, some did not. Just stop and think about Donna Carr, teen hours out of Giants Hole with a fractured skull. Henry Mares, out of Maskhill/Oxlow cavern. Those were Derbyshire. .In 1967 in Yorkshire,at the Mossdale tragedy, I nearly lost my Dad. Never mind the six that died. Cave rescue was a part of my childhood; I knew none other. Rob K

Thanks for commenting, Robert. Amazing how bit by bit over time we are hearing from people like you who knew these stories as part of their childhood through family involvement. So pleased that through the blog we are able to continue building on the story 😉 Very best wishes. Judy

After reading that Fred Davies of the Catterick Dales Club had died recently, it reminded me of other ‘Dales Club’ members. My caving tutor Boyd Potts introduced me into the club and to a career in caving. Boyd is sadly no longer with us, nor is Ralph Johnson a DCRO member, who assisted on the rescue so vividly described above. Neil Moss was a member of the ‘Dales Club’, too. The ‘Dales Club’ no longer exists except in the memories of its past members…

Thank you so much for reading and also sharing that snippet of news – great that we can keep adding memories and detail to the story.

Ron Peters (married to Norma) is still alive and living in Ferrers Way, Allestree, Derby. My mum was one of the Peters family and I can remember her talking about the heroic attempts to free Neil Moss. I am just sorting out names and addresses for Christmas cards when I came across your fascinating and well told story.

When I was 11 (I am now 60)I was on a walking holiday with Belper Scouts when 4 of us came across an interesting character camping below Pevril castle and amongst other more fanciful stories he told us about the caver stuck for ever. I though it was a fanciful story until I read “one last breath” and googled it.

Your article was really enlightening and stripped away fact for conjecture over the tragic events

I was only 15 and living in the West of Ireland at the time. We prayed and hoped that he would be rescued. We listened to each News Bulletin on Radio Éireann as the rescue progressed, always hoping for good news but sadly it was not to be.

Over the ensuing years I have often thought of him and his last terrifying moments. So young and yet so determined to take risks that ultimately benefitted others.

May he Rest In Peace.

EAMONN RYAN

At the time all of this was unfolding I was a three year old child living in a police house in Buxton. Still to this day I can remember my father telling my mother that the potholer(as my Dad described him) would be buried in situ.

I can’t even describe the nightmares that followed

Steve Troy

I lived nearby in Combs for 32 years and like many local people, I love the Winnats and learned about the young couple who were robbed and murdered by miners about two hundred years ago.

But I’d also heard of a single caver who went into a cave on the Winnats, got stuck, and was down there for a week. It was said he could be heard screaming and, indeed could sometimes still be heard screaming now. The story suggested that he was a middle-aged man who was climbing alone.

Then, early in 2020, a local man told me that the story I had heard was wrong In so many ways

The caver was 20 years old, climbing with a group and became stuck in a narrow tunnel. His name was Neil Moss and his body remains in the tunnel now called Moss’s Cavern.

I was shocked and moved to hear the true story and so. I’m sure. would you be. Search for his name in Google and remember him. his family and friends forever. So sad. RIP Neil.

I was fascinated to find this clear, factual report on an event I feared had been forgotten.

. I was a 19yr old member of Yorkshire Cave Rescue at the time called out by the police to attend.

By the time I arrived from 50 miles away many people had already in attendance. They were looking for someone slender who might be able to reach Neil sadly, I did not fit that requirement and so spent the day assisting moving equipment.

Unknown to me at the time another member of my Club the Chairman Bob Leakey who was a cave diver and one other diver subsequently got close to Neil from below but by that time it was too late to save him and they withdrew.

I pass the Cavern from time to time and have visited it twice, each time the memory returns.

Geoff Driver. Just watched Thirteen about the successful cave rescue. It brought back all the memories of Neil Moss, his death and the sad loss to his family, friends and caving. I was one of the many (some say too many) volunteers involved moving the oxygen cylinders. I am sure that there are still a few of us about, (now 81) that the Netflix film and the sad memories, will keep awake at nights. Thank you for your detailed and comprehensive article. One of my daughters is active with the Buxton Mountain Rescue so you could say we still have a connection. I wish you all your readers well, safe caving and safe return home

Thanks Geoff. Oddly, I had watched Thirteen Lives myself as your comment landed and remembered the Neil Moss story. Seeing the film of the Thai rescue really brought home to me what everyone must have gone through back then and such a sad outcome. Glad you enjoyed the article and good to hear you continue to have a connection through Buxton team. Stay safe and keep well. Judy

My dad (now aged 94) worked with Les Salmon and has told this story to us on many occasions. He remembers Les as being a lovely man.

I was in Castleton staying at the YHA on that tragic weekend with my cycling friends, the horror of the situation is still with me even though I was just a casual observer. An experience that put me off caves and potholes for a lifetime.

Rest in peace to those 6 who died in the Mossdale cave tragedy, they tried their best to beat the flood to it.

I was 7 years old, living in Leeds at the time of this tragedy. I remember it because my parents owned a fish and chip shop and all the customers talked about it and the failed rescue attempts. My mother was very upset and made me promise never to go potholing (as if, at 7).

I read Stephen Booth’s book not knowing about his reference to Neill Moss. It brought the memories flooding back. I wrote to Booth about my recollections and received a reply from him.

The story featured on TV, probably over 20 years ago and I managed to make a recording of it which I still have somewhere.

This is a comment from one of the very first group of cavers to be called out on the Neil Moss rescue. We were all members of the Eldon Pothole club and part of the then Derbyshire Cave Rescue Organise we all lived in Buxton .Oh yes there was a cave rescue organisation with cavers from all the caving cubs being part of this. The problems which gave huge problems later on came about because the police instead of using the then call out system abanded it and put the call out over the radio. This resulted in hundreds of” cavers” and non cavers flooding into Castleton and creating chaos.

This group were Phil Wildgoose, Clive Hockenhull, John Needham, Roy Fryer, another member, Jim Dunn, had attended earlier after being taken to the cave by one of the original cavers. Other Eldon club members soon were contacted and came to Peak Cavern soon after

We were called out at about 1.00 am after the White Hall outdoor pursuits centre had been informed by the police that they were wanted to go to Peak Cavern on a cave rescue. White hall knew us as we used to help with thier caving instructing. They organised transport to go round, get us out of bed, then to take us to Castleton to arrive at Peak Cavern about 2.30am. When we arrived at Peak Cavern we found a number of cavers from the original party, many police and a small lorry full of small (yes small) bottles of oxygen together with a long length of garden hose.

We were informed by the cavers from the original group about the situation in the shaft, and that the air was very bad. They had thought if oxygen could be be pumped down the shaft this would improve the conditions and then cavers could perhaps get down to Neil.

We changed changed into Goon Suits took two bottles each, and the hose, and took them into the chamber. Arriving in the chamber which in those day had a buatifull calcite flowstone slope at the backof the chamber. The shaft itself is in the righthand wall with the entrance not much larger than an (older) fireplace. Some ,cavers from the original group were still in the chamber ( looking very tired) they were Les Salmon, Ken Pearce, Dr Peter Crabtree

The situation in the cavern was very difficult with no one not really knowing what to do. We tried to get the bottles connected up to the “garden hose” which was very very difficult but did just about managed. Some one had to try this crazey system and this trial fell to our youngest member Roy Fryer who was 17 years old, very slim but a very good caver, Roy was the very first to try the hose and oxygen system and he has never been menioned before. Roy tried to hold the hose next to his face to breath the oxygen, he managed to get as far as the bends and then we heard. him gasping for breath. With difficulty we pulled him back to the top of the shaft, he was not in the best of heath. We realised that only a much slimmer caver could get round the 2 bends and some way conecting the tubing up to the a mask was required. All this time other people were begining to arrive and various other salutions, enlarging the shaft top, trying to find away in the stream at the bottom of the calcite slope were being tried. Very fortunatly the group of cavers from Orpheas Caving Club arrived in the cavern (I think 5 of them) . In this group was Ron Peters who also was a smallish very good caver. Time was going quickly and Ron said he wanted to try to get down the shaft. We had improved the hose/ oxygen conection a bit and Ron secured the hose slightly entered the shaft (on a life line), he got into the bends, past the first and nearly round the second. At this point he was gasping for breath and manged to get out of the shaft with aid of the life line. He recovered and went in again this time further passed the bends where he found the end of the life which had been tied round Neil but had broken when the original cavers were trying to pull him free. Ron managed to tie his own life line onto Neils and we tried to pull him up. We did manage to lift him about 2 feet when the rope broke again: unfortunatly that was the last time Neil moved. Ron managed with very great difficulty to get out of the shaft, but again insisted in trying once more. He took of some of his clothing went into the shaft, got into real breathing problems but just managed to get out once again. He was in real distress for some time before going out of the cave and walking past a large group of reporters with out them realising what he had just done , even taking a photo of him walking out of the cave.

Ron was awarded The GM and if anyone deserved it he did. Many people were very critical of DCRO after who they said had messed up the call out of cavers resulting in hundreds of cavers arriving in Castleton. Completly unfounded, it was because the police had released the call that cavers were wanted at the rescue attempt. The result being a very difficult meeting in Castleton where the DCRO secretary resigned and I took on the position. John Needham (still going strong

My mum named me after him. I was born 15/04/1959, and she told me the story when I was older.