Man + Mountain

A review of the Sir Chris Bonington exhibition at Rheged, and a mountain rescue tale

Ask most people in the UK to name a famous British mountaineer and they’ll say Sir Chris Bonington. This time last year, media reporting of his view that mountain rescue is ‘a sport’, in which our volunteer team members engage because they ‘enjoy the thrill’, stirred a great deal of debate on and offline (not least amongst ourselves).

As we noted at the time, we suspected his comments were said with tongue firmly stuffed in cheek and the flurry of media interest provided an opportunity to tell it like it really is and set the record straight about the nature of mountain rescue.

Many of us know from personal experience that Sir Chris has long been a firm advocate for mountain rescue. We even have a little tale of our own, courtesy of ‘Risking Life and Limb‘, which chronicles the history of the first fifty years of mountain rescue in the Ogwen Valley. It’s the story of a little known involvement between a much younger Chris Bonington and the fledgling mountain rescue team. But we’ll come back to that.

In the meantime, now in his 80s, Sir Chris continues to write about the mountains. An archive of his many adventures is now with the Mountain Heritage Trust and at the heart of the current Man + Mountain exhibition at Keswick Museum. Sally Seed went along to check it out.

‘The exhibition covers Sir Chris’s life as well as his various expeditions and the changes in mountaineering during his lifetime. One of the things that really struck me was that he’s one of very few survivors (along with Doug Scott) from a generation of climbers who conquered many of the high mountains, high walls and high challenges on our planet in a short period of just decades in the 20th century.

‘As someone who more or less remembers seeing the televised ascent of the Old Man of Hoy in 1967, it made me feel pretty old to see the reports and pictures from Sir Chris’s return with Leo Houlding to climb it again in 2016 – at 80 years of age.

‘But, to go back to the beginning, the exhibition include letters and postcards from a young Chris Bonington to his family and it’s clear he opted for the RAF for his National Service in the hope of moving into mountain rescue. He’d already caught the climbing bug after a trip to Snowdon in 1951 and then climbs at Harrison’s Rocks near Tunbridge Wells in Kent. Instead, he joined the Royal Tank Regiment after officer training at Sandhurst and managed to combine that with a life of climbing expeditions, including his (failed first) attempt on the North Face of the Eiger in 1957.

‘The exhibition covers plenty of Himalayan expeditions, with lots of Everest information, as well as trips to Greenland (with Robin Knox-Johnston in 1990) and elsewhere. There’s an interesting timeline about Everest in the bay window of the museum, overlooking the park, which starts with Everest being identified as the highest mountain in 1852 and ending up with today’s expedition permit statistics – 371 Nepalese permits this year and nearly 100 more from China!

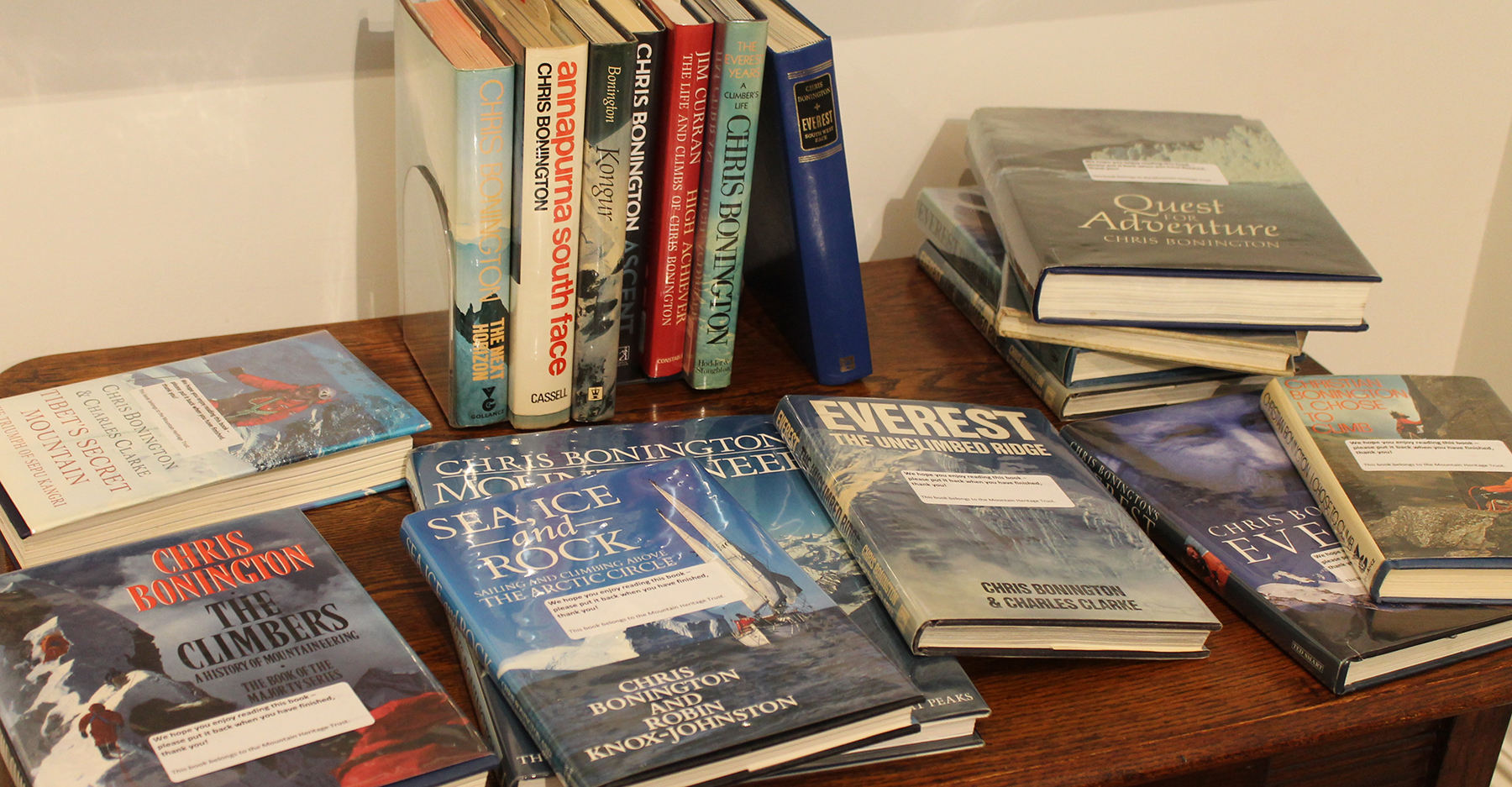

‘There’s a collection of Sir Chris’s books set out in a mock-up of his office at home and a fascinating case of his equipment – not only a brick-sized mobile phone but also a camera that he lost on the NE Ridge of Everest in 1982, found by Russell Brice on a later expedition and returned to Sir Chris in January 2018.

‘But the things that really struck me related to mountaineering equipment – the changes, the continuity and also the involvement of mountaineers in developing kit that’s now become standard. Climbing boots have changed a lot from hobnailed ones in 1955 through to Pierre Allain (PA) climbing shoes, but crampons have hardly changed at all. Duvet jackets, mittens, tents and harnesses are all featured in the exhibition (with credits to Don Whillans for a lot of the developments), and it was great to watch some of the younger visitors to the museum trying on the bulkier samples and then asking how you could climb a mountain wearing them. Not easily, was the obvious answer.

‘The dressing up box of mountain gear is just one of the interactive aspects of the exhibition – you can tell it’s been professionally designed to offer an interesting few hours for families on a wet weather day in Keswick. There are ropes and climbing harnesses to try out, a shadow board of traditional and modern rock climbing gear to be matched up and an Everest expedition tent to be explored. Certainly the young people who were there when I visited seemed fascinated and engrossed in the displays.

‘It’s sometimes easy to forget just how much Sir Chris Bonington has achieved in his 80+ years – and what it has meant for British mountaineering. Man + Mountain is a great reminder – so if you’re looking for something to entertain the family this half term, why not drop in and have a look for yourself?’

Man + Mountain Chris Bonington runs until Sunday 6 January at Keswick Museum on Station Road in Keswick CA12 4NF. It’s open from 10am to 4pm daily, the parallel Mountain Heritage Trust exhibition is British Women Climb (extended to January 2019) and there’s a great café downstairs run by West House, a Cumbrian charity for adults with learning difficulties.

But what about that mountain rescue connection (mountain rescue being the reason we’re here, after all)?

In 2015, when I was working my way through the Ogwen archives to write ‘Risking Life and Limb‘, a story came to light about an enthusiastic young man called Chris Bonington, just starting out on his adventures, many mountains ago.

Five years earlier, in October 2009, one of the Ogwen team founders, Ron James, recalled how ‘he once helped world renowned climber Sir Chris Bonington off the face of Tryfan when the pair were both teenagers’. Bonington too recalls the incident.

It was 1952. Still at school in Hampstead, he’d just completed his A-levels when he persuaded his mother to write a sick note to say he was in bed with flu, so he could squeeze a few days climbing in North Wales.

‘Off I went, climbing with a Scottish pal, Mick Noon. We went up to Terrace Wall to do Scars Climb. It was a straight VS then but it’s now classified as a hard VS. We’d plimsolls on our feet and a few slings round our necks. Our protection was a few runners over minuscule rocky spikes.

‘We just kept going. My leading standard then was about hard VS so I thought I’ll cream this one. I was having to do a bit of layback but there was nothing for my feet and I fell off. Came hurtling down. All the runners fell out. At the bottom is a grassy angled slope. I tumbled down that too.

‘I think I was slightly concussed, I’d damaged my arm and sprained my wrist. But I was able to walk down helped by various people – Ron being one of them. It’s amazing since then how many people reckon they saw me fall!

‘I was taken to the docs in Bethesda – it may have been Ron who took me. My memory is that the doc patched me up and the next day I hitched back to London. Then of course, I had to explain how I had a patched-up head and a patched-up arm when I was supposed to be at home in bed with flu!’

His mother, he says, was ‘amazingly calm and cool’ about all his various adventures.

He later spent the summer of 1963 in Snowdonia doing his ‘board’ – thankfully without further mishap – ultimately becoming secretary of the Sandhurst Climbing Club, so it holds a special place in his heart. And, at the team’s special anniversary dinner in March 2015, Sir Chris was principal guest, sealing an association with mountain rescue which had begun so many years before on the Tryfan rock.